Think About Replacement Now

If you’re like most people, you’re unlikely to go out looking for a water heater until your existing one fails. That will happen at the worst possible time — like just after guests arrive for a week-long visit. You’ll have to rush out and put in whatever is available, without taking the time to look for a water heater that best fits your needs and offers real energy efficiency. A much better approach is to do some research now.

Explore the options and decide what type of water heater you want — gas or electric, storage or demand, stand-alone or integrated with your heating system, etc. Figure out the proper size for your household, not just in terms of gallon capacity, but first-hour rating as well. This is particularly important with newer energy-efficient technologies. (See “Sizing Your Water Heater.”)

If possible, replace your existing water heater before it fails. Most water heaters have a lifespan of 10–15 years. If yours is up there in age, have your plumber take a look at it and advise you on how much useful life it has left. If it’s in bad shape, replace it now before it starts leaking or the burner stops working. In fact, it often makes sense to replace an inefficient water heater even if it’s in good shape. The energy savings alone could pay for the new water heater after just a few years, and you’ll be happy knowing that you are dumping fewer pollutants into the air and less money down the drain.

Selecting a New Water Heater

Whether you’re replacing a worn-out existing water heater or looking for the best model for a new house you’re building, choose carefully. Look for a water heater that satisfies your hot water needs and uses as little energy as possible. Often you can substantially reduce your hot water needs through water conservation efforts (see “Conserve Water”).

Storage Water Heaters

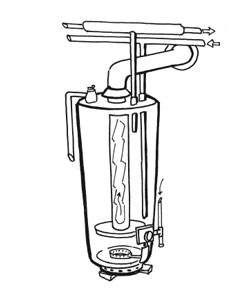

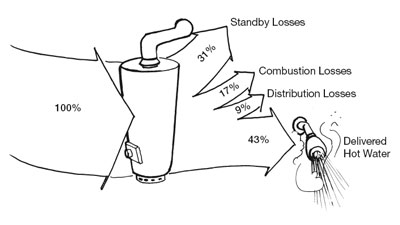

Storage water heaters are by far the most common type of water heater in use in the U.S. today. Ranging in size from 20 to 80 gallons (or larger) and fueled by electricity, natural gas, propane, or oil, storage water heaters work by heating water in an insulated tank. When you turn on the hot water tap, hot water is pulled out of the top of the water heater and cold water flows into the bottom to replace it. The hot water is always there, ready for use. Because heat is lost through the walls of the storage tank (standby heat losses) and in the pipes after you’ve turned the faucet off (distribution losses), energy is consumed even when no hot water is being used. New energy-efficient storage water heaters contain higher levels of insulation around the tank to reduce this standby heat loss. As for distribution losses— a problem common to all types of water heaters, look in the section on “Upgrading Your Existing Water Heater” for tips.

Efficiency and tank size. The energy efficiency of a storage water heater is indicated by its energy factor (EF), an overall measure of efficiency based on the assumed use of 64 gallons of hot water per day, regardless of tank size. The first national appliance efficiency standards for water heaters took effect in 1990. Updated standards, effective in 2015, are summarized in Table 6.1.

In a conventional gas storage water heater, less than 50% of the fuel energy reaches the point of use. New efficient water heaters can help reduce this excess heat loss.

| Tank Size | Gas* | Oil* | Electric* |

| 30 | .63 | .62 | .95 |

| 40 | .62 | .60 | .95 |

| 50 | .60 | .59 | .95 |

| 60 | .75 | .57 | 2.00 |

*Minimum Energy Factor (EF) as of 2015

All other things being equal, the smaller the water heater tank, the higher the efficiency rating. Compared to small tanks, large tanks have a greater surface area, which increases heat loss from the tank and decreases the energy efficiency somewhat, as mentioned above. If your utility company offers off-peak electric rates and you’d like to use them, you may need to buy a larger water heater to provide carry-over hot water for periods when electricity is not available under this “tariff.”

The most efficient conventional gas-fired storage water heaters are ENERGY STAR models with energy factors between 0.67 and 0.70, corresponding to estimated gas use of 214 to 230 therms/year. No residential-rated condensing water heaters (energy factors 0.80 or higher) are yet available, but small commercial-rated models are marketed for residential use. These have input capacity greater than 75,000 British thermal unit per hour (Btuh). Look for the “thermal efficiency” rating rather than EF, with values of 0.90 and above.

The minimum efficiency of electric resistance storage water heaters is about 0.90 (depending on tank volume), and the best available are 0.95 EF. We do not recommend the use of electric resistance water heaters due to the high operating costs. A new electric water heater uses about 10 times more electricity than an average new refrigerator! Fortunately, heat pump water heaters using less than half as much electricity as conventional electric resistance water heaters are now available from several manufacturers—use the Enervee Score or check the ENERGY STAR lists for detailed information. If you use electricity for water heating, consider installing a heat pump water heater. Look at how the costs compare over the life of a standard water heater in “Comparing the True Cost of Water Heaters.”

Sealed combustion. For safety concerns as well as energy efficiency, look for gas-fired water heater units with sealed combustion or power venting. Sealed combustion (or “direct vent”) is a two-pipe system — one pipe brings outside air directly to the water heater; and the second pipe exhausts combustion gases directly to the outside. This completely separates combustion air from house air. Power-vented units use a fan to pull (or push) air through the water heater — cooled combustion gases are vented to the outside, typically through a side-of-the-house vent. Power-direct vent units combine a two-pipe system with a fan to assist in exhausting combustion gases.

In very tight houses, drawing combustion air from the house and passively venting flue gases up the chimney can sometimes result in lower air pressure inside the house (see Building Envelope). In turn, this can lead to “backdrafting,” a situation when the air pressure inside is so low that the chimney airflow reverses and dangerous combustion gases are drawn into the house.

Demand Water Heaters

Demand or instantaneous water heaters do not have a storage tank. A gas burner or electric element heats water only when there is a demand. Hot water never runs out, but the flow rate (gallons of hot water per minute [gpm]) may be limited. By minimizing standby losses from the tank, energy consumption can be reduced by 10–15%. Before buying a demand water heater, though, be aware that they aren’t appropriate for every situation.

The largest readily available gas-fired demand water heaters can supply about 5 gallons of hot water per minute with a temperature rise of 77°F (58° to 135°F, for example). 77°F is the basis for industry calculations. This would support two simultaneous showers, or a bit more if the hot water is “mixed down” with a lot of cold water. If you’ve installed a low-flow showerhead (see “Conserve Water” below) and won’t need to do a load of laundry or dishes while someone is taking a shower, then 4–5 gpm might be fine. But if you have a couple of teenagers in the house, or if you need hot water for several tasks, a demand water heater might require staging some uses.

Newer instantaneous gas water heaters modulate their output over a broad range; typical outputs might range from 15,000 to 180,000 Btuh—a 12:1 range in hot water output, depending on demand (washing hands versus filling a clothes washer). This is an improvement over earlier models. However, there are still some significant issues with tankless water heaters. First, they have a minimum water flow rate of 0.5 to 0.75 gallons/minute, and turn off or don’t start at the lower flow rates used for hand washing and similar tasks. In some situations, this can lead to “cold water plugs” in the hot water supply lines, which leads to alternating delivery of hot and cold water — not regarded as a comfortable way to shower! They also require regular maintenance, and performance in hard water areas is not well studied.

Electric demand water heaters provide less hot water. A standard size model requires about 11 kW per gpm to achieve a 77º F temperature rise. Large units may require 40 to 60 amps at 220 volts, beyond the wired capacity of conventional houses. If you want to consider an electric unit, make sure your electrical wiring can handle the job before you make a purchase. However, a small electric demand unit might make good sense in an addition or remote area of the house, thereby eliminating the heat losses through the hot water pipes to that area. These losses often account for a large percentage of the energy wasted in water heating, regardless of the technology of the water heater. If you’re using energy to heat water that has to make it a hundred feet across the house, a small electric demand water heater placed under the sink to boost the temperature of incoming water locally may be a good idea.

Demand water heaters make the most sense in homes with one or two occupants, and in households with small and easily coordinated hot water requirements. Without modulating temperature control (above), you and your family may find yourselves unhappy with fluctuating water temperatures — particularly if you have your own well water system with varying pressure.

With gas-fired demand water heaters, keep in mind that a pilot light can waste a lot of energy. In gas storage water heaters, energy from the pilot light is not all wasted because it heats the water in the tank. This is not the case with demand water heaters. A 500 Btuh pilot light can consume 20 therms of gas per year, offsetting some of the savings you achieve by eliminating standby losses of a storage water heater. To solve this problem, you can keep the pilot light off most of the time, and turn it on when you need hot water — a routine that should work fine in a vacation home, but not in a regular household. Among new demand water heaters sold in the United States, standing pilots have become very rare as almost all models use electronic ignition.

Manufacturers provide different specifications for demand water heaters: energy input (Btuh for gas, kilowatts [kW] for electric); temperature rise achievable at the rated flow; flow rate at the listed temperature rise; minimum flow rate required to fire the heating elements; availability of a modulating temperature control; and maximum water pressure. In comparing different models, be aware that you aren’t always looking at direct comparisons, especially with temperature rise and flow rate. For example, while one model might list the flow rate at a 100°F temperature rise, another might list the flow rate at 70°. Until there are industry-standard ratings for temperature rise and flow rates, it will be difficult to compare the performance of products from different companies. Many manufacturers now publish energy factor ratings for these products, and this information should make for easier comparisons. If you choose a tankless unit, look for one with EF 0.8 (gas).

What’s a Tankless Coil?

Do not confuse a tankless coil with a tankless water heater or an indirect water heater. Tankless coils use the home’s existing boiler — they are most common with older boilers — as the heat source for water heating with no storage tank. When hot water is drawn from the tap, the water circulates through a heat exchanger in the boiler. Tankless coils work great as long as the boiler is running regularly (during the winter months), but during summer, spring, and fall, the boiler has to cycle on and off frequently, wasting a lot of energy. Instead, ACEEE recommends an “indirect” tank-type storage water heater, or a free-standing storage water heater.

Ready to Buy? Check out the Enervee Marketplace. ACEEE’s partner, Enervee, makes it simple to find the best deals from your favorite retailers on the most energy efficient electric and gas water heaters that meet your needs.

Visit ENERGY STAR for a full list of qualified models.

The Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute lists high-efficiency water heaters on their website.

Advanced Water Heating Systems

Some of the most efficient water heaters find creative sources of heat— such as other heating equipment, outside air, or the sun — to provide hot water with less fuel. These include heat pump water heaters, indirect water heaters, integrated space/water heaters, and solar water heaters.

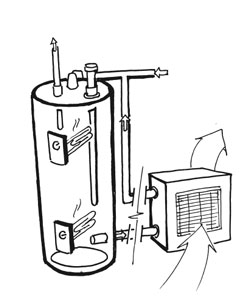

Heat pump water heaters. More efficient than electric resistance models, heat pump water heaters use electricity to move heat from one place to another rather than generating the heat directly (see discussion on heat pumps in Heating and in Cooling). The heat source is outside air or air in the room where the unit is located. Refrigerant fluid and a compressor are used to transfer heat into an insulated storage tank. While the efficiency is higher, so is the cost to purchase and maintain these units. Heat pump water heaters are available with built-in water tanks called integral units, or as add-ons to existing electric resistance hot water tanks. A heat pump water heater uses one-third to one-half as much electricity as a conventional electric resistance water heater. In warm climates they may do even better.

Households using electric water heating and a heat pump for space conditioning can reduce water heating costs by installing a “hybrid” heat pump system. Fully integrated single-unit systems are one option, or an existing heat pump and storage water heater can be retrofit with a specially designed add-on heat pump water heater module. Hybrid air- and ground-source heat pump systems are available.

Hybrid gas water heaters. Broadly speaking, the term refers to water heaters with more than two gallons storage, but less storage than expected from output capacity. They feature a condensing burner smaller than used on whole-house tankless units and enough storage to have high first hour ratings. The smaller burner means they generally will not require new gas lines for retrofit installations. Because the burner is > 75,000 Btuh, they will be classed and rated as commercial products, although marketed for residential use.

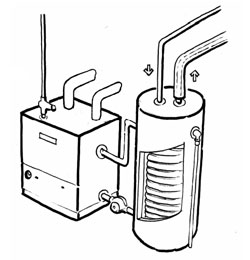

Indirect water heaters. Indirect water heaters generally use the home’s boiler as the heat source, circulating water from the boiler through a heat exchanger in a separate insulated tank. Since hot water is stored in an insulated storage tank, the boiler does not have to turn on and off as frequently, improving its fuel economy. Electronic controls determine when water in the tank falls below a preset temperature and trigger the boiler to heat the water as long as needed. The more sophisticated of these systems rely on a heat purge cycle to circulate leftover heat remaining in the heat exchanger into the water storage tank after the boiler shuts down, thereby further improving overall system efficiency.

Indirect water heaters, when used in combination with new high-efficiency boilers, are usually the least expensive way to provide hot water (see “Comparing the True Costs of Water Heaters”). These systems can be purchased in an integrated form, incorporating the boiler and water heater with controls, or as separate components. Gas-, oil-, and propane-fired systems are available. Any form of hydronic space heating — hydronic baseboards, radiators, or radiant heat — can be provided by boiler systems.

Integrated “combi” water heaters. If you’re building a new home or upgrading your heating system at the same time you’re choosing a new water heater, you might consider a combination water heater and space heating system. These systems, also called dual integrated appliances, put water heating and space heating functions in one package. Space heating is provided via warm-air distribution.

The efficiency of a combination water heater with integrated space heating is given by its combined annual efficiency, which is based on the AFUE of the space heating component and the energy factor of the water heating component. Look for combined annual efficiencies of 0.85 (85%) or higher.

Combination appliances feature a powerful water heater, with space heating provided as the supplemental end-use. Heated water from the water heater tank passes through a heat exchanger in a central air handler to heat air. The fan blows this heated air into the ducts to heat the home. Many combination systems of this type are available at low initial costs, but space and water heating efficiency is often less than that of conventional systems. Models incorporating a high-efficiency condensing water heater, such as the Polaris® by American Water Heater, are exceptions. These models realize efficiency gains over traditional equipment, at 90% combined efficiency. Another approach, introduced in the U.S. by Rheem, uses a tankless water heater as the “engine” for both space heating and hot water.

As you may have guessed, proper sizing of a combination appliance is very important for economical performance, since both space heating and water heating are given from one “box.” Product manufacturers should be able to identify your local distributors and contractors who are familiar with these products and their installation.

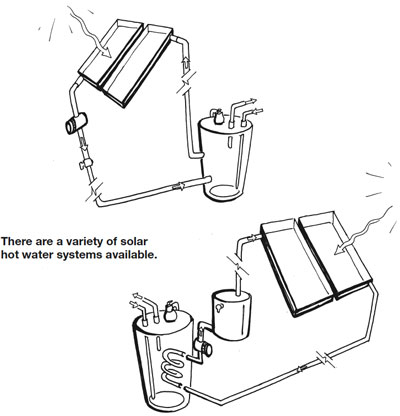

Solar water heaters. As the name implies, these use energy from the sun to heat water, or help heat water. Solar water heaters can be a great investment because they offer a virtually cost-free and renewable energy source for one of your home’s top energy users. But because the feasibility and benefits of a solar water heater will vary based on variables such as where you live, which way your roof is facing, and how many people live in your house, it takes some extra savvy to know what your costs and savings will be.

A solar water heater consists of a solar thermal collector attached to a south-facing sloped roof or wall, a well-insulated storage tank, and a fluid system that connects the two. It is usually preferable to use a two-tank system in which the solar water heater circulates water through the collectors and back into a separate tank that then “preheats” the conventional water heater. The distance between the collector and the tank, or the amount of finished space the loop must traverse in a retrofit installation, impacts the method and cost of installation.

Solar collectors can consist of an insulated glass box with a flat metal plate absorber that is painted black, or a set of parallel glass-encased metal tubes that absorb solar heat. Some collectors use a parabolic mirror to concentrate sunlight onto the tube. A fluid circulates between the solar collector and the tank either using a pump (active system) or natural convection (passive system). The most important difference among solar water heaters is the system’s ability to resist freezing. If temperatures rarely go below freezing, water can circulate freely from the collector to the tank (open-loop system). But usually, it is safest to circulate another freeze-resistant fluid through the collector and transfer the heat to water using a heat exchanger in the tank (closed-loop system). An alternative strategy, which is simpler and often cheaper, is the “drainback” system, which is like an open system except it allows water to return to the tank as soon as the pump shuts off.

Solar water heaters are less common than they were during the 1970s and early 1980s when they were supported by early tax credits, but the units available today tend to be considerably less expensive and more reliable. The initial cost of a solar water heater is still much higher than other competing technologies, but if you can make the upfront investment, it can save 50–75% of your water heating energy over the long term in most climates. For example, in New England it is possible to have a complete system that will provide one-half of the hot water requirements for a typical family of four for around $5,000 installed. In most areas of the country, you will pay back the full price of the solar water heater over the course of its life. So it usually depends on whether you have the money and interest to make the upfront investment. See how a solar water heater stacks up against other technologies over its life cycle in Table 6.2.

Installation cost in your area may vary. Areas that receive sun consistently for 3 or more seasons will not only save more energy, but consumers are likely to have more products to choose from at lower costs. Plus, new federal tax credits (set to run through 2016) coupled with state-level incentives available in a number of jurisdictions present additional incentives for purchasing solar water heaters.

To see whether incentives for solar technologies are offered in your state, contact the Solar Energy Industries Association.

For a list of manufacturers in your area, check with the Solar Rating and Certification Corporation.

Also check the Florida Solar Energy Center for a list of rated high-quality solar water heaters.

If you are building a new house, it is to your advantage to have a south-sloping roof for easier installation of a solar water heater. At low cost, you can have the best place “pre-plumbed” or “roughed-in” so “dry” pipes are in place if you later want to install a solar water heater.

If you have extra money to invest now and want to do more for the environment, a solar water heater can be a good choice in most areas today. But make sure you find a qualified installer who can properly design and size the back-up water heating system. Solar water heaters can be particularly effective if they are designed for three-season use, with your heating system providing hot water during the winter months.

State of the Art Water Heating

On-demand recirculation systems eliminate the energy, time, and water wasted when waiting for hot water to reach the faucet. The best systems add a connecting loop, a pump, and a controller between the hot and cold water lines at the furthest fixture from the water heater. When activated by the push of a button, a pump rapidly circulates hot water to the fixture, and the roomtemperature water in the pipes is returned to the water heater. These systems are relatively easy do-it-yourself installations. Available products include the ACT Metlund® D’Mand® and Taco D’Mand® Systems.

Solar-powered circulators are available for solar water heaters — once you’re using solar power for water heating, why not also supplement the electricity needed to run the system? These are available from several manufacturers. If you are considering a solar water heater, ask your installer about this option. Drainwater recovery devices can be installed in the drainage lines beneath showers and other hot water uses to recapture some of the heat returning to the pipe and transfer it back to the water heater. The most common example of this type of product is the GFX (gravity film exchange) by Doucette Industries.

Small-diameter and “Home Run” piping systems are gaining popularity as an alternative to traditional copper piping. Instead of having a single wide-diameter pipe that branches off to different end-uses, individual polyethylene (PEX) tubes are run from a central manifold to each end-use. Fewer fittings and elbows reduce friction and wait time. Learn more at PPFA.

Comparing the True Costs of Water Heaters

There are a number of important considerations when deciding what type of water heater you should buy: fuel type, efficiency, configuration (storage, demand, combination), size, and cost. The information above covers most of these issues. Cost, however, needs some additional discussion. There are really two costs you need to look at: purchase price and operating cost.

It may be tempting when you’re buying a water heater simply to look for a model that is inexpensive to buy, and ignore the operating cost. This course is penny-wise and pound-foolish. Often, the least expensive water heaters upfront are the most expensive to operate over the long run. Life-cycle costs, which take into account both the initial costs and operating costs of different water heaters, provide a much more costs for the most common types of water heaters under typical operating conditions are shown in this table.

Life-Cycle Costs for 13-Year Operation of Different Types of Water Heaters

| Water heater type | Storage Volume (Gallons) | Efficiency(1) (EF) | Cost (1) | Yearly energy cost (2) | Life (years) | Cost over 13 years (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional gas storage | 40 | 0.60 | $850 | $350 | 13 | $5,394 |

| High-efficiency gas storage | 40 | 0.65 | $1,025 | $323 | 13 | $5,220 |

| Condensing gas storage | 50 | 0.80 | $2,000 | $262 | 13 | $5,408 |

| Conventional oil-fired storage | 30 | 0.55 | $1,400 | $654 | 8 | $11,299 |

| Minimum Efficiency electric storage | 50 | 0.90 | $750 | $463 | 13 | $6,769 |

| High-eff. electric storage | 50 | 0.95 | $820 | $439 | 13 | $6,528 |

| Demand gas (no pilot) | <2 | 0.82 | $1,600 | $228 | 13 | $4,560 |

| Electric heat pump water heater | 50 | 2.20 | $1,660 | $190 | 13 | $4,125 |

| Solar with electric back-up | n/a | 1.20 | $4,800 | $175 | 20 | $7,072 |

(1) Costs are rough estimates, including installation, based on internal and other surveys.

(2) Based on hot water needs for typical family of four and energy costs of 9.5¢/kWh for electricity, $1.40/therm for gas, and $2.40/gallon for oil.

From the table, we see that when both purchase and operating costs are taken into account, one of the least expensive systems to buy (conventional electric storage) is one of the most costly to operate over its expected 13-year life. An electric heat pump water heater, though expensive to purchase, has a much lower cost over the long term. A solar water heating system, which costs the most to buy, has the lowest yearly operating cost among electric systems.

Sizing Your Water Heater

To determine how big a storage water heater you need, you should first estimate your family’s peak-hour demand. To do this, estimate what time of day (morning or evening) your family is likely to require the greatest amount of hot water. Then calculate the maximum expected hot water demand using Table 6.3. Note that this does not provide an estimate of your family’s total daily use, only the peak hourly use. Also, the values in this table do not consider water conservation measures, like water-saving showerheads and faucet aerators that can reduce hot water use for each activity. If you have a new home, have upgraded to water-saving fixtures, or installed an ENERGY STAR clothes washer or dishwasher, your peak demand will be lower.

The ability of a water heater to meet peak demands for hot water is indicated by its first-hour rating. This rating accounts for the effects of tank size and how quickly cold water is heated. In some cases, a water heater with a small tank but powerful burner can have a higher first-hour rating than one with a large tank and less powerful burner. Ask appliance dealers for the first-hour ratings of appliances they sell or check the manufacturer’s literature.

Buying too large a storage water heater will reduce energy performance by increasing the standby losses. If gas- or oil-fired, larger systems will also lose more heat up the flue. Demand water heaters should be sized according to the required gpm flow rate and temperature rise during the winter required for your largest expected hot water fixture (usually a shower). (See “Demand Water Heaters.”)

With solar water heaters, you should discuss your requirements carefully with the solar water heating salesperson. You will need to size both the solar hot water system itself and the back-up electric or gas water heater. It generally makes the most sense to size a solar water heater to provide almost all of the hot water needed during a peak summer day. This is economically sound, but will require supplemental water heating in other seasons and on cloudy days.

Installing a Water Heater

Select an installation contractor carefully. Make sure that he or she has experience with the type of system you want to install. If the system is integrated with your heating system, have your heating contractor put in the water heater. To get a good value, ask for bids from several contractors and evaluate the bids carefully. Consider warranties, service, and reputation as well as the price.

Storage water heaters will lose less heat if they are located in a relatively warm area. Also try to minimize the length of piping runs to your kitchen and bathrooms. The best location is a centralized one, not too far from any of your hot water taps.

When the water heater is being installed, make sure heat traps or one-way valves are installed on both the hot and cold water lines to cut down on losses through the pipes. Without heat traps, hot water rises and cold water falls within the pipes, allowing heat from the water heater to be lost to the surroundings. Heat traps cost around $30 and will save $15–30 per year. Some new water heaters have built-in heat traps. If heat traps are not installed, you should insulate several feet of the cold water pipe closest to the water heater in addition to the hot water pipes. Even with heat traps, insulate the cold water line between the water tank and heat trap.